The curse of Masakado

Who would have thought that Otemachi, Tokyo’s financial and business district that sits on some of the most expensive land in the world, seems to be forever haunted by the vengeful spirit of a samurai who died over a thousand years ago?

This sounds too good to be true. Let’s investigate.

Otemachi district is a place where many large corporations and newspaper companies established their headquarters.

But today we’re not here to mingle with bankers, we’re here to find something far more sinister (if that’s even possible). At one of the intersections, you can find a sign pointing to “Masakado-kubizuka”. This translates into something like “the mound of Masakado’s decapitated head” — which is believed to mark the final resting place of the head of a samurai named Taira no Masakado.

Following the sign, we arrive to a small secluded area nestled among the skyscrapers.

A large stone lantern suggests this place isn’t something from modern times.

There are two stone signs near the entrance to the site. The one on the left says “Historic site Masakadozuka”, the one on the right “Preservation monument, Minister of Finance Kawada Isao” (we’ll get back to this one later).

Let’s walk up the slope.

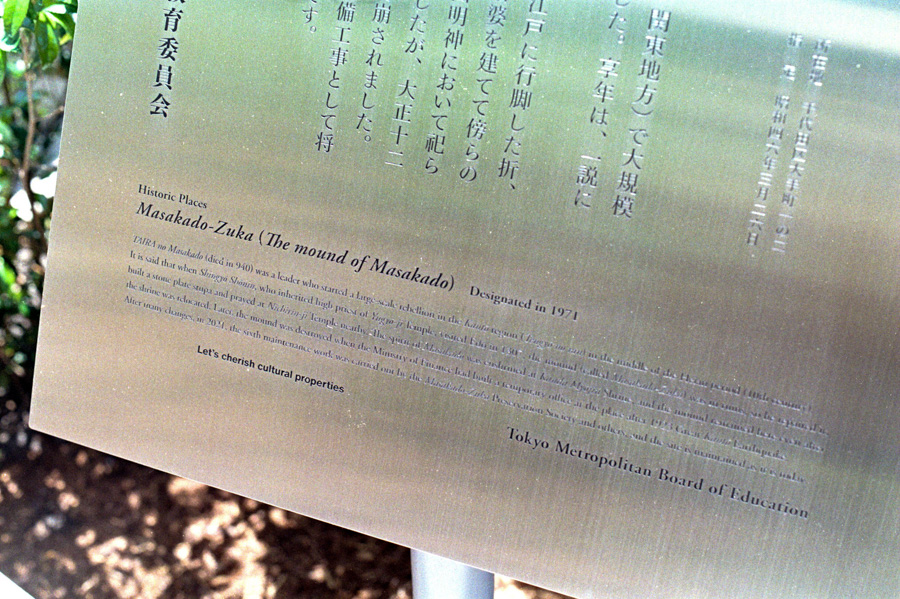

There is a plaque with brief historical information in Japanese and English about this place.

And here it is…

…the mound of Taira no Masakado.

The turbulent story begins in the Heian period, around the end of the eighth century. Japan’s capital was moved from Nara to Kyoto, which remained the center of government for the next four centuries. In the year 939, a wealthy samurai named Taira no Masakado — a real figure — led a rebellion against the government in Kyoto with plans to set up an independent state. He named an alternative capital in Sashima (today Chiba Prefecture), and declared himself the “New Emperor”.

His uprising didn’t last long. The next year he was killed and beheaded.

His head was brought to Kyoto and displayed near a river bank as a warning for other would-be rebels.

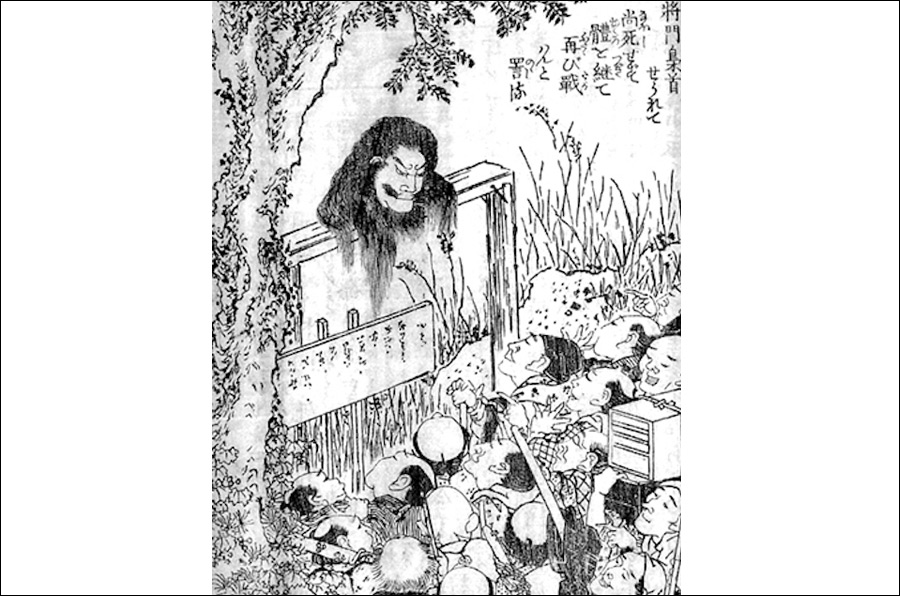

As the legend goes, three months later strange things began to happen. His head remained unchanged, the eyes looked especially furious, and the teeth kept grinding for months thereafter. Every night the head cried, “Where is my body? Come here! Fight me again!”.

One night, the head is believed to have taken off and flown — yes, flown! — toward Masakado’s home in what is now Ibaraki Prefecture, frantically searching its body. On the way, it was shot down by an arrow fired by a monk at Atsuta Shrine. The head crashed in an area called Shibazaki, a small fishing village (which later became Edo and then Tokyo). The villagers picked it up, washed it and buried it beneath a mound in Kanda Myojin Shrine which was located in what is now Otemachi.

Later during the Edo period, the shrine was moved to a new site, but the mound with Masakado’s head was left behind where it remained until this day. It has been widely believed that causing disrespect to Masakado’s grave would be punished with disaster and misfortune. Indeed, strange phenomena began to happen.

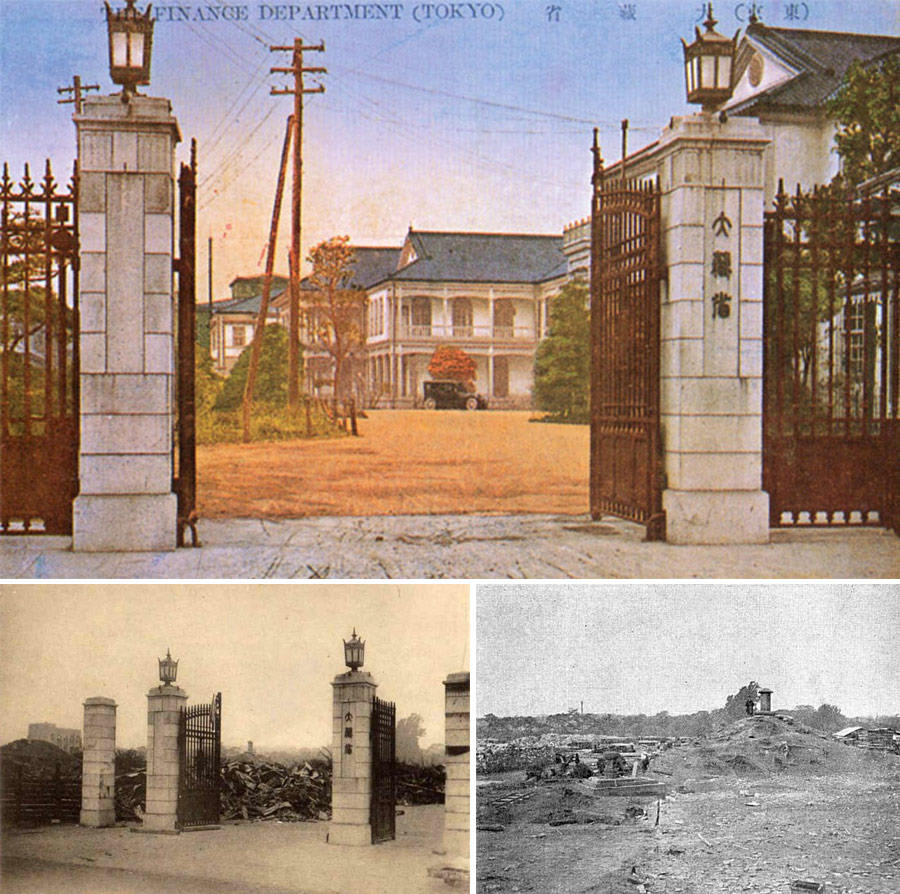

Since the Meiji period, the area was owned by the Finance Ministry. The mound of Masakado was located on its grounds. In 1923, during the Great Kanto Earthquake which devastated much of Tokyo, the ministry burned down. Oddly enough, the mound seemed to have avoided damage, as seen from the old photos below.

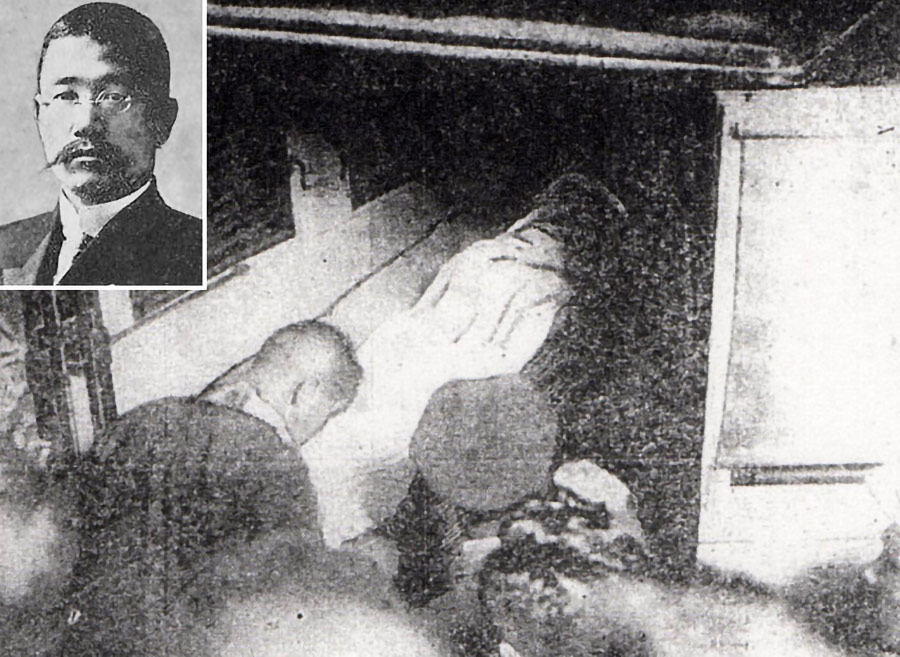

Two and a half months later, the Finance Ministry decided to rebuild the site, erecting a temporary structure. At that time, there was no Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties, and they destroyed the tombs. A building was constructed over Masakado’s grave. This proved to be a very bad decision — reportedly fourteen officials of the ministry, including the finance minister Hajami Seiji, started dying one after another within two years, and the reconstruction was halted.

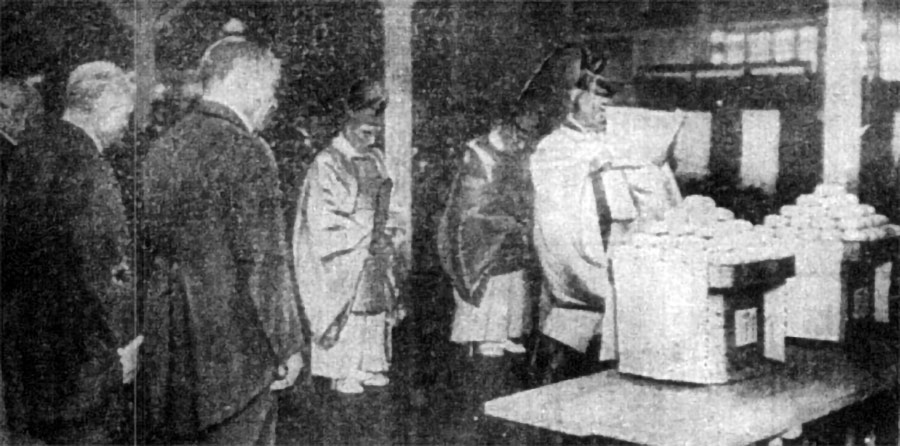

Newspapers at the time reported about the deaths; however, the articles did not mention anything about the “curse of Masakado”. Nevertheless, the rumors began to spread and even politicians became frightened. Eventually, they demolished the building that was on the location of the grave. They built hedges, restored the lantern and the cornerstones, and a special remembrance ceremony was held. Newspapers reported about “bureaucrats who apologize to Masakado even in the present age of advanced science”.

On June 20, 1940, the new headquarters of the Finance Ministry (sounds like Masakado certainly had a problem with the finance ministry!) burned to the ground upon catching fire from a lightning strike that struck the adjacent Civil Aviation Bureau. The chilling part is that the year 1940 was exactly a one thousand years anniversary of Masakado’s death in 940. The Finance Minister at the time, Kawada Isao, announced a special remembrance ceremony for Masakado. They erected another preservation monument marking the site, which still stands today, and the angry spirit of Masakado has calmed down for a while. Or so they thought.

In 1945, after the end of World War II, the American military — not knowing the history of the site — cleared the area to create a parking lot. A parking lot! It is said that this resulted in another tragedy where a bulldozer flipped over, killing the driver. The accident was recorded in the archives of Kanda Myojin Shrine, but not published in any newspapers. As such, it is believed that there was indeed an accident, but exact details are unknown. Later in 1961, the parking area was demolished to make space for new construction. Just in case, each corner was purified with ritual salt, and the mound was once more dedicated to Taira no Masakado.

However, once the construction was completed, employees of the Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan that worked in the rooms facing the tomb fell sick one after another. The bank went bankrupt in 1998. Companies in the vicinity jointly formed the “Taira no Masakado Memorial Committee” to help maintain the grave. Sanwa Bank ordered an employee to visit and pray at the site once a month. Even the bank president is said to have donated in the tomb’s donation box because his building cast the tomb into shadow. Mitsubishi UFJ Bank opened an account under the name of “Taira no Masakado” which is used by a local volunteer group looking after the site.

—

Today, people still come here to pray. You are likely to see someone visiting at any time during daytime (but maybe not so at night, obviously). TV crews pray here every time before they film something related to the history of Masakado.

The high-rise building that’s presently adjacent to the site, called Otemachi One, is a business building housing offices of several companies, a hotel, shops and restaurants.

The mound of Masakado went under major renovation in 2020, with utmost care being taken with the maintenance. With its brand new appearance, you would never have guessed how much history lies behind it. The wall around the site is decorated with light-colored wooden beams holding decorations made of glass. Do you think their effort will appease Masakado’s spirit?

Only time will tell. But next time you walk around this place, remember that the real boss of Tokyo’s business district is not the CEO who sits behind the mahogany desk on the 50th floor — it’s the unforgiving spirit of a timeless samurai that lurks under the ground in this small sacred corner of Otemachi.